A California labor law might upend trucking

But it could be the biggest boon for drivers' working conditions in decades

It was a busy week, so this note typically coming to you on Wednesdays is arriving on a Sunday evening. Regular programming to resume this week.

I’m writing this newsletter in full view of an unmoving cargo ship that has been sitting outside of my window for DAYS. When will the container crisis end?!

Nice view though!

This week, I’d like to talk about a fascinating, complicated issue: how California’s AB5 law ended up not regulating the gig economy that seemed to be its original target, but may instead spark massive changes in trucking.

Last month, a federal court in California ruled to apply AB5 to trucking fleets. This isn’t getting a lot of chatter online or in print, which I think is a mistake.

If America’s trucking companies are required to hire all drivers as employees in California, this will likely drive up prices on the many, many things we grow and transport from that state. It will also provide perhaps the biggest jump in truck drivers’ working conditions in decades.

First, a primer on AB5 (which you might know as Prop 22)

California’s top court decided in a landmark case in 2018 that most workers for companies were automatically employees. Companies would “bear the burden” of establishing a worker was an independent contractor through a test.

To establish that court decision into law and further codify it, California’s state legislature passed Assembly Bill 5 in 2019. (You can read more about AB5 here.)

The law was angled at workers in Big Tech’s “gig economy” — think drivers for Uber and Lyft, delivery drivers for GrubHub/Seamless, and grocery pickers for Instacart. These workers are deemed as “independent contractors.” They don’t receive overtime pay, minimum wage guarantees, health insurance, or a slew of other benefits that typical workers receive.

AB5 will never deliver those benefits to gig workers, thanks to California Proposition 22. Voted into law last year, Prop 22 says Uber, Lyft, and other ride share or delivery companies may continue to categorize its drivers as independent contractors. (Those firms also backed a $200 million campaign to sidestep having to provide drivers with labor protections.)

AB5 may crush small trucking fleets instead

AB5 wasn’t going to affect trucking — thanks to a 2020 court decision based on a 1994 federal law, which bans states from making laws that affect freight prices.

That changed in April. A federal court in California overturned last year’s court decision. Now, trucking companies may soon be required to hire truck drivers as employees. (There’s currently an injunction on the ruling. Industry folks are perhaps intending on taking it to the Supreme Court.)

Fleets are anticipating the responsibility of providing drivers with sick pay, overtime, health insurance, and other benefits. Facing the possibility of having to ratchet up pay and benefits, executives are freaking out.

Trucking fleets — which operate in a highly-competitive, ultra-low-margin industry — are able to keep their labor costs unusually low. AB5 would undermine a lot of that. Drivers are paid per mile. They rarely receive paid rest breaks or overtime pay; though, under federal labor laws, they are allowed to work up to 70 hours every eight days. Some drivers say they ultimately earn less than minimum wage.

Save for the most prestigious fleets (such as, weirdly, Walmart), truck drivers infrequently enjoy paid time off or paid sick leave.

Trucking companies are also less likely to offer health insurance to their drivers. Around 38% of truck drivers are uninsured, compared to 17% of other working Americans.

California’s many, many tiny trucking companies will likely die out if they have to provide these benefits to drivers. Several amicus briefs filed last year to exclude trucking from AB5 emphasized that small trucking fleets may be unable to function sans the independent contractor model for truckers. Larger fleets, which have more cash on hand, would likely be able to finance this all.

You might declare, ‘Sucks for the small fleets! Bring on the benefits!’

I would recommend you wait before you utter this!

One brief from the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association indicates how disastrous it would be to let small trucking companies die off in California, which comprises 15% of the country’s GDP.

The state comprises nearly a quarter of the US’ agriculture output and up to one-half of its container-trade imports. (That means basically everything that’s made in China.) California’s products often move to the rest of the country via truck, and there’s a “staggering” number of goods that travel within the state of California, OODIA wrote.

Meanwhile, nearly 85% (!) of trucking companies nationwide consist of six or fewer power units. Some 70,000 of these small trucking fleets exist in California, said OOIDA.

If these trucking companies were to suddenly vanish, the capacity of trucks would also sink. And a plunge in trucking supply can pinch consumers in myriad ways — whether it’s more expensive lumber for homes or pricier Amazon Prime fees.

We’ve seen this before.

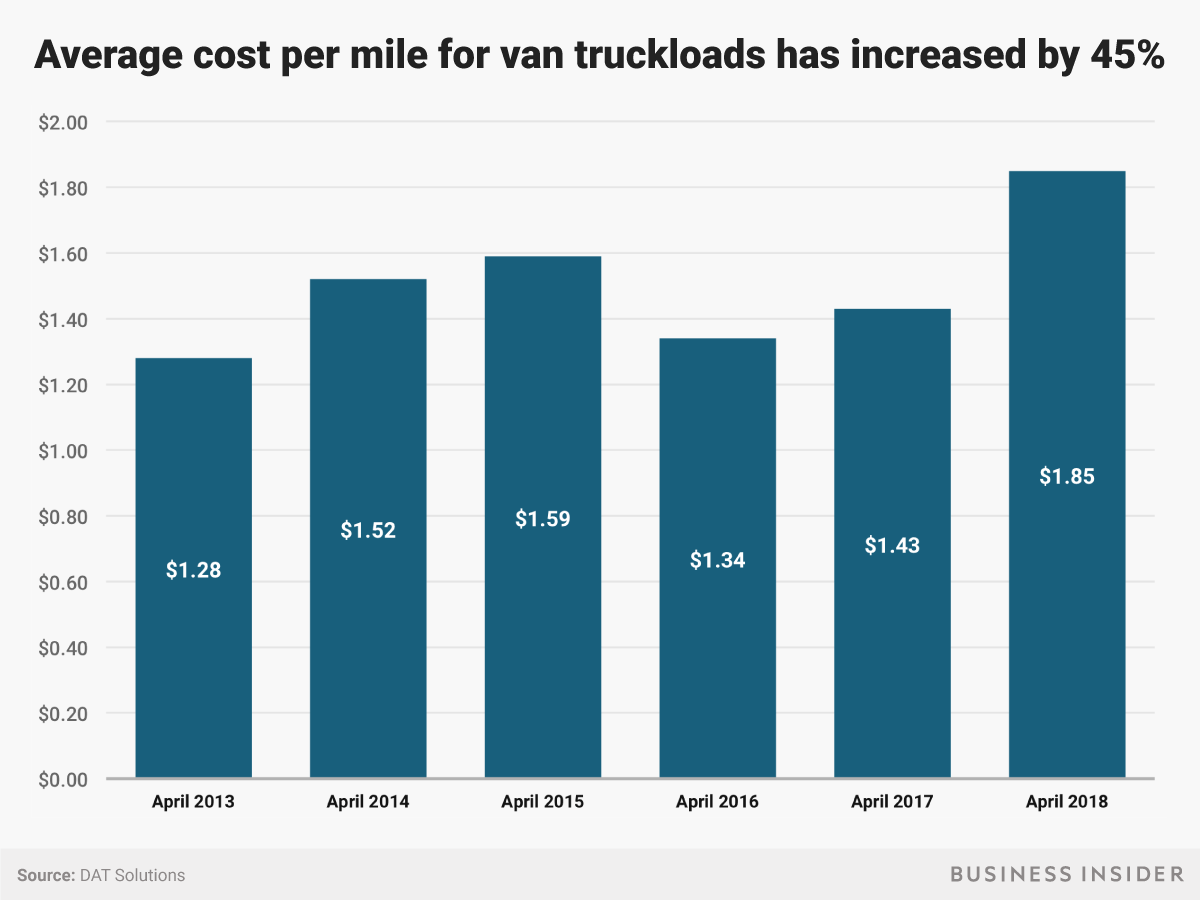

In 2018, truck drivers nationwide were required to use electronic logging devices in their cabins, requiring them to actually follow federal hours of service rules. That effectively limited the number of trucks on the road, and made common consumer goods that much more expensive.

(Of course, as we saw in 2018, this drop in trucking capacity would likely be short-term. Many truck drivers for smaller fleets would presumably find work at the larger companies.)

This could be the biggest jump in benefits for truck drivers yet

It’s typically through legal decisions that truck drivers see upticks in their working conditions. A few recent examples from recent years:

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled last year that companies cannot force their so-called contract workers, particularly those involved in interstate commerce such as truck drivers, to settle disputes through forced arbitration.

Courts across the US have forced trucking giants like PAM, Walmart, Werner, and C.R. England to issue major payouts to drivers who allege they were paid less than minimum wage. These decisions pointed at the idea that drivers deserve to be paid for each hour they spend working, even if they may not be driving.

The AB5 ruling, which promises a slew of benefits and pay to drivers in one fell swoop, may be bigger than all of those decisions put together.

Indeed, Teamsters, which has seen its trucker membership drop in the past decades, called last month’s AB5 ruling “a massive victory for California’s truck drivers, who for far too long have faced exploitation and misclassification at the hands of trucking companies that place corporate profit ahead of drivers’ safety and well-being.”

Read more here on how truck drivers’ wages and working conditions have tumbled in recent decades. I hope you guys already know about this by now!

We’re moving closer to what one economist envisioned as the best outcome for drivers. Stephen Burks at the University of Minnesota, and formerly a truck driver, told me last year there’s really only one way to improve the livelihood of America’s two million truck drivers: Make everything more expensive.

"It would be a radical upheaval of demanding retailers charge more to the consumers and therefore freight rates can go up and all those sort of things," Burks said. "But that seems like the only way for truck drivers get paid more: consumers everywhere just pay more for their things to offset those transportation costs."

Hmmm… what do you think of that? Would you be okay with paying more for stuff if it means drivers could make a better living? It reminds me of debates presented in my college economic classes: Should we continue to export manufacturing jobs abroad, making everything cheaper, even if it sparks domestic economic instability?

Leave a comment below or send me an email at rpremack@businessinsider.com. I’ll feature the best remarks in my next MODES!